Most Disturbing Death Rituals in Human History

December 11, 2017

It is often said that death is the great equalizer; it knows no hierarchy and does not willfully spare a soul.

In order to deal with the inevitable phantasm of life wilting away, humanity has devised all kinds of dark, foreboding rituals to better swallow the bitter truth.

Fear of death lies at the root of our collective obsession with all that is grotesque and morbid. And various societal traditions have played a huge part in helping us to exorcise our demons.

The following are some of the most weirdly disturbing rites ever, proof that there is no limit to the twisted dreams and nightmarescapes our brains are capable of devising.

1. Cannibalism

For some, the only way to fittingly bid a beloved adieu would be by eating them.

The technical anthropological term is actually “endocannibalism,” and this frightful ritual was typically performed in select tribes of Papa New Guinea.

Essentially, what would occur is that after death, members of the tribe would put together a festival, wherein everyone would be encouraged to cook, and then eat the recently deceased.

The macabre tradition was seen as a way of encouraging others to make peace with the idea of dying and normalizing it as much as possible.

Of course, one might think that this act is anything but normal.

While the festival is definitely an aberration from what today would be considered a proper way to mourn, different variations on the same theme appear in other cultures, albeit in less outwardly violent ways.

2. Sky Burials

A little different from the tribal cannibalism featured above, this ritual is still colored by the idea that mourning the flesh is equal to eating the flesh.

Tibetan Buddhists practice ritual dissection, or “Sky Burials,” which entails chopping up the dead into small pieces and giving the remains to animals, especially birds.

Predictably, vultures stand to gain the most from this mode of dealing with death.

At first, this kind of burial might seem unnaturally uncaring and brutal. But the reality is that it is completely in keeping with Buddhism, which does not believe in commemorating a dead body.

The flesh is merely a vessel for the soul. Maintaining the “circle of life” by providing a sustainable diet for other life forms is seen as a compassionate gesture.

3. Sati

While this once common practice has been banned in India for a long, long time, “Sati” often saw recently widowed women immolating themselves on their husband’s funeral pyre.

A similar practice is said to have occurred amongst the Ancient Egyptians, Greeks, Goths, and other societies.

The roots of the bleak custom remain rather unclear, but it could have something to do with a commonly held belief that it provided a way for husband and wife to peacefully enter the afterlife together.

Other scholars have seen it as a more practical attempt to prevent wives from killing their husbands for money.

The macabre ritual is disturbing on many levels, especially in that it wasn’t always voluntary on the part of women.

They were sometimes thrown into the fire against their will by other people in attendance; burnt alive at the stake.

The tragic imagery these processions would produce was not that of a distraught wife mourning for her husband, but rather a collective witch-hunt.

4. Viking Death Ritual

Perhaps the worst case of the macabre intersecting with deeply misogynistic rituals can be found in the way Vikings dealt with the death of a chief.

According to various historical records, the customs following a leader’s passing are incredible for their stark brutality.

The chief’s body would first be placed in a temporary grave for ten days while new clothes were being knitted and sewn for him to don. Meanwhile, a slave girl would offer to join him in the afterlife, by first being given insane amounts of intoxicating drinks.

Once the cremation ceremony started, the girl would go from tent to tent, having sex with every man in the village.

During these encounters – which clearly are closer to a societally sanctioned form of rape – the men would gleefully declare “Tell your master I did this because of my love for him.”

The girl would then be taken to a tent wherein she would be forced to have sex with six Vikings, violently strangled with a length of rope, and stabbed by the village matriarch.

The disgusting ritual would finally end when the bodies of the chief and slave girl were placed on a wooden ship and set alight, in an attempt to ensure that she would serve her master in the afterlife.

The copious sexual rites were a bizarre attempt to transform the chief’s life force.

Perhaps some of these historical records exaggerated the worst customs of the Vikings for raunchy effect, but regardless of the veracity of this particular claim: they maintained a vivid reputation in pop culture for a reason.

5. The Danse Macabre

The namesake of this article, the “Danse Macabre,” or Dance of Death is a type of allegorical art form manifesting itself in theater, dance, and music, dealing with the haunting specter of death.

With origins in France, and beginning in the Middle Ages, the Danse would typically consist of a personification of death summoning people of different backgrounds – usually a nobleman, a child, the pope, and a simple peasant – to dance towards a gravesite or cemetery.

Skeletons would be reanimated to join in on the dance during the long procession to a mass grave, the ghastly imagery an attempt to normalize death.

The Danse Macabre most likely has roots in the fear and tragedy spawned by the 100-Year War, wherein death never differentiated between kings and laborers.

All were one, and the tradition is meant to underscore the fragility of life and the inherent vanity of material possessions.

The denizens of Medieval Europe thus became incredibly well-attuned to death during this period, given the popularity of the Danse Macabre as a uniquely bleak, albeit rejuvenating custom both in life and in art.

This fact is further underscored in the plethora of Medieval architecture which still survives in various areas throughout Europe, with homes and chapels made up of skulls and bones; an eerie reminder of humankind’s inevitable fate.

6. Mourning Jewelry & Death Photography

The Victorian era is noted for significant advancements in technology, societal infrastructure, and cultural norms.

However, it also gave birth to more offbeat traditions, particularly when it came to accepting death as part of the cycle of life.

One notable – and ever so morbid – fad was the making of memorial jewelry to commemorate the passing of a beloved.

Before photography was discovered in the latter part of the Victorian age, snipping a thick lock of hair from the head of the deceased to create a locket, or braiding it into a kind of bizarre ornament was de rigueur.

While creating jewelry from a lock of hair may be seen as a bit romantic, more morbid creations were made using teeth and bones, and were incorporated into flashy adornments such as rings and cufflinks.

It seems that a serial killer could easily get away with various crimes given the nature of this peculiar tradition.

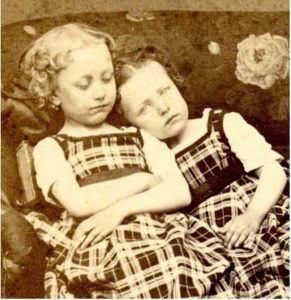

Later on, with the advent of photography came an even more macabre fashion: snapping a photo with the corpse of your loved one.

Countless images have survived this peculiar moment in history, documenting a little boy holding his dead brother for example; forcing the body to stand upright for the camera.

While both traditions can somehow be seen as a natural evolution of painting portraits to honor the memory of the deceased, they are still rather disturbing because of the darkness they conjure.

Dark Fascination

The rituals noted here range from the slightly quirky to the truly disgusting and twisted.

They all share a commonality: they envision a world wherein fear of death is the main driving impulse, and the variety of ways humanity has attempted to deal with the inevitable are rather mind-boggling in their originality.

Who says that life isn’t scarier than fiction?